Abigail Hing Wen has worn many hats. A lawyer by training, she spent years clerking on the D.C. circuit, working toward becoming a law professor.

“The next step would have been to write the law review article that would’ve been my calling card to go on the market,” she tells Kirkus over Zoom from her sunshiney Bay Area living room. On the wall behind her is evidence of a different path taken: prints of the covers of her three published books, as well as a poster for the recent film Love in Taipei, which is based on the first of the trilogy.

“My husband insisted on putting these up for me very recently,” Wen explains. “This is the first interview I’m taking with these in the background.”

The series of novels opens with Loveboat, Taipei, the story of Ever Wong, whose parents enroll her in Chien Tan, a Chinese language and culture program in Taipei, Taiwan, against her wishes. Her arc takes her on an exploration of identity as she seeks balance between her parents’ aspirations for her and her own dreams, modulated by the choice of romance with two very different boys, Rick and Xavier.

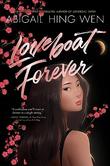

With the third and most recent installment, Loveboat Forever (HarperTeen, Nov. 7), readers return to Taipei six years later, this time in the company of Pearl Wong, Ever’s younger sister. Pearl is driven to attend Chien Tan after the explosive reaction to a video she posts on TikTok. A gifted pianist, she has a significant following on the video-sharing app for her classical renditions; when she shares a photo of herself at the piano wearing a traditional conical Chinese straw hat, she faces a severe backlash from those who feel she’s performing an offensive caricature of Chinese identity.

Wen spoke to Kirkus about the series, the new film, the complex give-and-take of immigrant identity, and the future of artificial intelligence. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

We enter the story with a timely inciting incident—that of a TikTok-fueled controversy.

Pearl is steeped in the classical music world, and it’s very much the music of Vienna, of Mozart and Beethoven, of Bach and Brahms. She loves these composers—classical music is in her blood—and she would really rather not think about being Asian American. Yet this social media blow-up requires her to think about who she is and where she comes from, and it’s not something she can escape.

That’s been true for me, too. For many years I would rather not have been Asian American; it would have been much easier to be like everyone else around me in Ohio. But over time, I came to realize there was something richer and deeper that I was missing out on, and I think that’s Pearl’s journey, too. Even if it’s thrust upon her, she begins to figure out how to make her culture her own.

I know some of your work has been on the ethics of technology, and specifically AI. How did that background influence your writing about social media in the book?

The internet polarizes people. It rewards controversy. In Pearl’s case, people piled on, and piled on, and then the algorithms pushed [her video] out so that it would be discovered by even more people who could get angry about it. That’s a huge negative to our social lives and to our mental health. I think that’s where our AI systems still need work. How do we encourage algorithms to promote healthy behaviors?

It can absolutely be done, but we have to make the choice not to reward certain behaviors. That does mean you have to make profits in different ways, and that requires creativity. But it’s not an impossible task; we just have to value it and prioritize it.

We see Pearl juggle in this book with what kind of life she wants for herself—what she values and what she wants to prioritize. This is especially evident when she visits her family’s ancestral home.

Growing up, the prevailing wisdom was, We are so lucky to have come to America for a better life. That was why my parents left [Asia], and that’s why a lot of immigrants come to America. And I think it was a better life in many ways. For my mom, she was the eleventh child, and I think the sixth girl in her family, and she was able to have opportunities in America as a woman she wouldn’t have had if she’d stayed home. But at the same time, when I went back to visit my family—I took a trip just like Pearl, to the Lim family village [in Fujian province, China], where my mom’s family is from—I experienced that amazing resonance of, Oh my God, these are all my relatives, and there are millions of Lims who have come out of this province. I didn’t know I had such a wide network of people out there in the world. I always felt that it was just the five of us in Ohio. Pearl has that revelation as well.

Growing up, the prevailing wisdom was, We are so lucky to have come to America for a better life. That was why my parents left [Asia], and that’s why a lot of immigrants come to America. And I think it was a better life in many ways. For my mom, she was the eleventh child, and I think the sixth girl in her family, and she was able to have opportunities in America as a woman she wouldn’t have had if she’d stayed home. But at the same time, when I went back to visit my family—I took a trip just like Pearl, to the Lim family village [in Fujian province, China], where my mom’s family is from—I experienced that amazing resonance of, Oh my God, these are all my relatives, and there are millions of Lims who have come out of this province. I didn’t know I had such a wide network of people out there in the world. I always felt that it was just the five of us in Ohio. Pearl has that revelation as well.

Over time, I came to realize it’s not so black and white. There are things you give up when you leave your family behind to move to another country, and there are benefits to living in a community of people who know you and know your family. But I think we build that as immigrants, too. When we come to a new place, we find people and we make connections, and that’s beautiful. We make friends with people we would never have made friends with.

For Pearl, part of the exploration is, Can we have all of it? Can we find a way to reclaim some of the things we’ve lost? In her story, that balance comes through music: She loves the piano, but she also comes to love the pipa.

How did it feel to work on the film Love in Taipei? Did it change your thoughts about the story you were telling?

Seeing what people took away, seeing how it was translated into a shorter film version, really made me appreciate how [Loveboat, Taipei] is about a girl coming to a deeper understanding of her family. The romance arc of the book ends in a different place than in the movie: She ends up with Rick in the book and Xavier in the film. That was a big question mark: Why is she ending up with Rick, when her parents actually like him? He’s the boy wonder; he’s what’s always been held up as a standard for her; he’s everything she’s supposed to achieve. The instinct is to rebel against that. But that’s her journey: She’s able to separate what she wants from what her parents want in a nuanced way. She can end up with the guy her parents like, but she can also choose dance, which her parents don’t want for her. With the film, that arc doesn’t quite go there, so that difference made me reflect on what made the book different. The South China Morning Post did a review that was about how Loveboat, Taipei was the first Asian American young adult novel in which the kids come to a deeper understanding of their parents. That is very much what I hope for in all my work: to bridge the gap between generations and between cultures.

Ilana Bensussen Epstein is a writer and filmmaker in Boston.