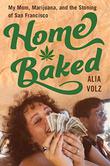

Alia Volz’s Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, April 20) is both a lively, well-written memoir of an unusual childhood and an insightful cultural history of the Bay Area in the 1970s and ’80s—as Kirkus’ reviewer puts it, a “love letter to San Francisco filled with profundity and pride.” At a time when possession of one marijuana plant could send you to jail, Volz’s mother built a business selling pot brownies to a bustling community of hippies and buskers, artists and actors, restaurateurs and shopkeepers. By the time she closed Sticky Fingers for good, AIDS was devastating that community and the brownies had become medicine.

Your mom grew up in Milwaukee, where she narrowly escaped getting busted for pot before heading to the West Coast in 1975. As you put it in the book, “she was like most everyone who traveled west hoping to reinvent themselves and ended up reinventing the West.”

The line, “Go west young man, and grow up with the country,” dates back to the gold rush. San Francisco was built on a series of mass migrations—including the Summer of Love and the techie invasion—that both destroyed and remade our culture. My mom came here hoping to change her own life and ended up changing the city.

Amazingly, every single decision she and your father made in building a 10,000-brownie-per-month business was based on consulting the I Ching. You say at the beginning of the book that you don’t believe in it—but considering their success, the book makes quite a case!

My parents believed that the I Ching kept them safe, and I wanted to make that feel as real and magical as it was to them. But my mom was also street-smart. When my parents fled San Francisco because of negative I Ching hexagrams, they were also conscious of Sticky Fingers Brownies getting too much media attention. They felt the city changing in the wake of the Milk/Moscone assassinations, the Jonestown massacre, and the riots. The I Ching told them what they already knew.

My parents believed that the I Ching kept them safe, and I wanted to make that feel as real and magical as it was to them. But my mom was also street-smart. When my parents fled San Francisco because of negative I Ching hexagrams, they were also conscious of Sticky Fingers Brownies getting too much media attention. They felt the city changing in the wake of the Milk/Moscone assassinations, the Jonestown massacre, and the riots. The I Ching told them what they already knew.

From infancy, you were surrounded by adults in altered states, whether it was marijuana, mushrooms, LSD, or cocaine. When you were old enough, you were drafted to help with the brownies. Yet you state many times that your mother was an excellent parent.

Certainly, some families are destroyed by drug use, but that didn’t happen to us. My mom was always present for me. Some memoirists represent alternative parenting as a kind of abuse, but I know plenty of hippie kids who came out fine. If you’re fine, you usually don’t write a memoir, so these stories aren’t told. No trauma, no drama. In my case, I have a larger drama to draw on.

You are incredibly kind about your father, too, though he was troubled and a less capable parent.

When I started this book 12 years ago, my dad and I were estranged. Over time, I realized that to tell this story properly, we had to have conversations that were decades overdue. In the course of developing his character and reconstructing his actions for the book—which we did together—we healed our relationship. It was brave of him to go there with me.

The historical information in Home Baked is backed up with pages of footnotes, and you have pretty granular detail in the personal story as well. You describe people’s clothes, moods, thoughts, and conversations in an immersive way that made me wonder how much was reporting and how much was imagination.

One of my models was The Devil in the White City, which reads like a novel, though every detail is rooted in research. Whenever I’m in someone’s head in Home Baked, that comes directly from an interview, and all the major players read the manuscript for accuracy. Along with historical archives and newspapers, I had access to hundreds of family photographs and a chronological archive of the illustrated bags they used for delivery.

And some of each are included in the book. The brownie bag that says “If all the world’s a stage, San Francisco is the cast party”—seems to capture the city you grew up in.

That bag from 1978 captured a moment when the city was bursting with creativity and life. But I was an infant then. I grew up during the AIDS years, when the cast members were fighting for their lives. We were left with this incredibly brave, raw humanity—and the healing power of community. More dramatic than ever, I guess, but utterly real.

Marion Winik is the author of The Big Book of the Dead and reviews for Kirkus, the Washington Post, and other publications.