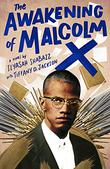

The Awakening of Malcolm X (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Jan. 5), based on the life of the legendary activist, was co-authored by his daughter Ilyasah Shabazz—a speaker, educator, and youth advocate—and YA author Tiffany D. Jackson, a Coretta Scott King–John Steptoe New Talent Award winner. The novel prompts readers to directly connect Malcolm X’s activism with present-day injustices. By focusing on the radical transformation he underwent during six years of imprisonment in his 20s, the book shows a young man on a journey of awakening to the systemic inequalities affecting him and his fellow inmates. This portrait of a man known for his unwavering commitment to speaking the truth, regardless of the cost, is deeply moving and powerfully relevant today. Shabazz, who as a 2-year-old was present when her father was assassinated, spoke with me over Zoom from her home in Westchester County, New York, and Jackson answered questions via email; the conversations have been edited for length and clarity.

Ilyasah, how do you feel your father’s story speaks to contemporary teens?

Ilyasah Shabazz: I think that what my father did is put a mirror up to America, and the world, about injustices. People are asking, Who is Malcolm X? because this is not the person that I remember hearing about in school or on the news. They’re curious because we’re seeing injustice—young people being killed with no accountability, police brutality, just so many things. His message is relevant because he spoke truth, and truth is timeless. He predicted just where we are right now: He said that young people will understand that those who’ve been in power have misused it. They’re ready to roll up their sleeves and make change, do the work that is necessary. He would never back down from truth—contrary to what has been written and said, my father had great integrity.

What do you hope teens will take away from reading the book?

IS: That intergenerational dialogue is important, the information that elders give to young people. It’s because of that that Malcolm was able to always be retrospective, to reflect on his time with his dad, his mom, his siblings, and remember their tutelage. Also understanding that Malcolm didn’t go to jail and miraculously become Malcolm X. He became Malcolm X because of the foundation that his parents provided. The importance of self-love, seeing yourself as a global citizen, seeing yourself as a member of humanity, the interconnectedness. And understanding the importance of literature, of history. Malcolm read everything you can imagine. He always had a book, even when he was on the streets of Harlem.

Why did you choose to focus on this time, when your father came to understand hard truths about society through his experience of the prison system?

IS: I wanted to make sure that we could understand the humanity of young people finding themselves in a tight spot. I wanted to make sure that we were able to look at inmates, not from the perspective of [crime] but looking at their humanity and understanding that certainly they’re crying, certainly they’re afraid, and sometimes even innocent. Bryan Stevenson, who is one of my heroes, said, we will not be judged on how we treat the rich and celebrated, we will be judged on how we treat the poor and the incarcerated. The course that I teach [at John Jay College of Criminal Justice] is Perspectives on Justice in the Africana World. America holds the highest population in prison in the world; 32% of the U.S. population is represented by African Americans and Latinos compared with 56% of the incarcerated population. The 13th Amendment allows the unpaid labor of prisoners, making the current prison industrial complex an extension of slavery and police controls an extension of slave patrols.

tight spot. I wanted to make sure that we were able to look at inmates, not from the perspective of [crime] but looking at their humanity and understanding that certainly they’re crying, certainly they’re afraid, and sometimes even innocent. Bryan Stevenson, who is one of my heroes, said, we will not be judged on how we treat the rich and celebrated, we will be judged on how we treat the poor and the incarcerated. The course that I teach [at John Jay College of Criminal Justice] is Perspectives on Justice in the Africana World. America holds the highest population in prison in the world; 32% of the U.S. population is represented by African Americans and Latinos compared with 56% of the incarcerated population. The 13th Amendment allows the unpaid labor of prisoners, making the current prison industrial complex an extension of slavery and police controls an extension of slave patrols.

You must have drawn on a lot of family stories.

IS: I thought about my nephew, who had a similar experience. It made it easier to come up with dialogue. Also, my aunt Hilda used to tell me so many stories about those days and how she felt after the Autobiography [of Malcolm X, written with Alex Haley] was completed and, reading it, how she felt [about] the image of her parents in the book. It was important for her that people knew that her father was the chapter president of [the Universal Negro Improvement Association]; that Marcus Garvey would come to their home; that her mother didn’t have a nervous breakdown [but was forcibly sectioned]—a lot of things. So, I wanted to make sure that all of the information that my aunt Hilda had shared, as well as my uncles Wilfred and Wesley, was included.

How did you choose Tiffany D. Jackson as your collaborator on the project?

IS: She came from TV [and] film, so I figured she’s going to be a visualist. This is really important, because one of the things I like to do in my books is make sure that you can see the story. I knew that she was a risk taker, that she did not bite her tongue. She was just so wonderful to work with; I feel so honored that I had the opportunity to work with her. We talked about the kind of story that I wanted to focus on: I needed to make sure that Malcolm wasn’t looked at as a criminal, that we understood who he was before he was incarcerated.

Tiffany, what is your process in writing historical novels?

Tiffany D. Jackson: The trick is to rely on the news, political climate, and setting to ground the characters. Once you have the established facts, you apply emotions, drive, hunger…which are timeless needs. I also reread Kekla Magoon’s X: A Novel [co-authored with Shabazz in 2015] to nail down the voice and watched a ton of Malcolm’s speeches and documentaries to capture his wit.

What were some of the challenges in writing about this complex individual whom readers probably know less well than other Black activists?

TDJ: I think the first challenge was to remind people how young Malcolm was during this period of his life. That he was very much still a kid who lost his way briefly. His development is considered “controversial” compared to some other activists, but I think that’s what makes the best type of example for kids: knowing mistakes can open a lane for greatness. His awakening is both raw and inspiring.

Did your feelings about Malcolm X change over the course of writing this book?

TDJ: There were so many instances where I had such astounding aha moments while reading some of his speeches and following his journey. But surprisingly, what stuck out to me the most was learning personal factoids, like his love of strawberry ice cream. We sometimes forget that a man that seems so [much like a] superman and leaves us so awestruck is really just that, a man, a human. That we all are.

Is there anything else that you would like to share?

TDJ: When writing this, I thought about the countless boys I’ve met in detention centers and tried to put myself in their shoes. How can we help inspire them by injecting Malcolm’s passion through the page?

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.