Years before Kawai Strong Washburn published a lick of fiction, he was a graduate student studying macroeconomics at Columbia University who found himself falling for “big L literature.” He took his first creative writing workshop —taught by then–MFA student Parul Seghal, now a top book critic at the New York Times—and knew he’d keep writing after that.

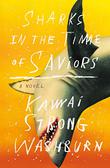

Short stories, a family, a career as a software engineer, and a decade under his belt, and now Washburn has published his debut novel, Sharks in the Time of Saviors (MCD/FSG, March 31). Set in his native Hawaii, the book tells the story of three siblings, at odds in part because their parents see one brother as having received a fearsome blessing from the sea.

As the siblings leave, one by one, for the mainland, they become progressively lost—but each also tries to find a way to reconnect with home.

Washburn spoke via Skype from his home office in Minneapolis.

How would you describe the family’s economic status?

I would say they’re in the working-class bracket. At different points in the story, they have jobs that are more or less viable in terms of allowing them to provide for the family, but at other times they’re just scraping by to make ends meet. A lot of people don’t realize how difficult economically it can be to live in Hawaii.

Yet the characters live in this tropical paradise.

Photo by Crystal Lieppa

Photo by Crystal Lieppa

There are some fantastic natural spaces in Hawaii that are still accessible to everybody: national parks, state parks. But in some cases, parts of the islands that had some of the most pristine and, especially for Native Hawaiians, sacred spaces have been converted into tourist-driven facilities—an amusement park or hotel or condominiums. You can grow up there and be living a blue-collar lifestyle and have a lot of access to natural beauty, but there can also be times when, if somebody has enough money, those things can be taken away from the local residents.

How do you see the role of Hawaiian spirituality and religion in the book?

The book doesn’t present a complete view of Native Hawaiian spirituality and religion. It’s written in a rotating first person, and each character has a flawed, incomplete understanding of their heritage and their culture. A lot of people in Hawaii can still not understand as much of the islands as they would like, and that’s a result of colonialism—there were formal attempts to annihilate Native Hawaiian culture. These characters are living with the legacy of that, which means they don’t have a full understanding of their religion. Over the course of the novel they’re trying to understand—what’s happening to us, and what does that mean, and what do we believe, and what’s real and what isn’t.

Each of the siblings—Dean, Nainoa, and Kaui—has a different relationship to the islands. Who do you most closely identify with?

There’s probably a little bit of each of them in me. I’m the least like Dean—leaving the islands and making it big as an athlete is his dream. Like Nainoa, there have been parts of the islands that have remained with me and have grown stronger the farther I’ve gotten away—he’s ultimately called to return. And Kaui—I have felt like an outsider in a lot of situations, not only because I grew up in the islands and then came to the continental United States, which are very different, but also because I was kind of shy and awkward. So I would say it’s a mix of Nainoa and Kaui.

There’s probably a little bit of each of them in me. I’m the least like Dean—leaving the islands and making it big as an athlete is his dream. Like Nainoa, there have been parts of the islands that have remained with me and have grown stronger the farther I’ve gotten away—he’s ultimately called to return. And Kaui—I have felt like an outsider in a lot of situations, not only because I grew up in the islands and then came to the continental United States, which are very different, but also because I was kind of shy and awkward. So I would say it’s a mix of Nainoa and Kaui.

Let’s talk about Kaui’s path—she studies to be an engineer but winds up on a farm in Hawaii trying to create regenerative agriculture.

I really want to talk about the themes of the book in a way that I hope spreads the conversation beyond just the story. About trying to build a sustainable future and learning from the Indigenous cultures that, in my belief, had some better understanding of their relationship with the natural world. When we look at things like climate change, we’re going to need to start turning back to some of these beliefs that were part of our history. We need to put them in the forefront so we have a better understanding of how we’re going to build a modern world that is sustainable, that is ecologically and socially just. It’s going to take all of us forming better communities and thinking about what we want the world to look like in the coming decades. I think this book speaks to that at some level, and I’m hoping that it becomes a launchpad for those sorts of discussions.

Carolyn Kellogg is the former books editor of the Los Angeles Times.