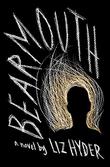

Set in a quasi-Victorian British coal mine filled with child laborers, Liz Hyder’s debut, Bearmouth (Norton Young Readers, Sept. 8), took the U.K. by storm after its release last year, winning a Waterstones Children’s Book Prize and the Branford Boase Award and being named a Times (U.K.) Best Children’s Book of the Year. This novel, narrated by gender-indeterminate Newt, is impossible to categorize, bearing elements of thrillers, historical fiction, and dystopian novels. Deep underground in unbearably oppressive conditions, Newt is taught to read and write by Thomas, a father figure, and the story is written in their idiosyncratic, phonetically rendered dialect. The workers attend Sunday services where they are reminded to pray to and obey “the Mayker,” a tremendous and imposing figure they perceive in the rocks. When Devlin, a new young miner, brings dangerous talk of revolution, the uneasy peace between mine owner and exploited laborers is poised for upset. Hyder spoke with me from her home in Shropshire, England; the conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

I understand it was a visit to a mine that inspired the story.

It was a slate mine just south of Harlech on the north coast [of Wales] called the Llanfair Slate Caverns. It was chucking it down [raining], our hike in the hills was canceled, so we went down the slate cavern. It has an amazing atmosphere—you go in, and they give you a hard hat and a huge torch [flashlight], mind your head, and off you go! There’s something delightful about that childish element of feeling like you’re exploring rather than being guided. It’s very dark, obviously, and there are bits of old mining equipment, like old wagons and trolleys—all metal, completely corroded—the sound of dripping, and moss.

It was a slate mine just south of Harlech on the north coast [of Wales] called the Llanfair Slate Caverns. It was chucking it down [raining], our hike in the hills was canceled, so we went down the slate cavern. It has an amazing atmosphere—you go in, and they give you a hard hat and a huge torch [flashlight], mind your head, and off you go! There’s something delightful about that childish element of feeling like you’re exploring rather than being guided. It’s very dark, obviously, and there are bits of old mining equipment, like old wagons and trolleys—all metal, completely corroded—the sound of dripping, and moss.

There were a couple of things that really struck me: One was that the boys did have their right nostrils slit [as in the book]. It’s a kind of cult element, so you can see who belongs. I found that such an odd, contradictory thing, really, as it’s also from that same environment that we have the workers unions. And there is a figure in the rocks—if you squint you can see it—and the workers used to doff their caps to it as they came in and out. I found again that was like the cult element. I felt sad and angry when I came home, angry about exploitation and about how exploitation has rebranded itself. I had a really intense reaction, and then I thought, well, actually, it would be a great place to set a story. It’s an interesting part of British history because when we think of mining, a lot of people think it’s like the miners’ strikes in the ’70s or Thatcher—effectively the beginning of the end of mining. The more I found out, the more I thought, this is fascinating and awful, and I can’t believe we aren’t taught about this properly. The Industrial Revolution was built on exploitation.

Apart from visiting lots of mines, what research did you do?

It was interesting talking to people who had been miners because British mines before we closed them, Welsh mines in particular, were the safest in the world, nothing like what it was back in Victorian times. But some of the stuff they said [was relevant] about the way that you can read the space [for signs of danger]; you are looking out for certain things, if the wood is creaking, if there is a drip that you hadn’t noticed before. Their senses are much more aware. I read a lot of firsthand accounts from the children at the time as well. It is horrifying—such young children. The youngest one that I found that was killed in a mining explosion is just registered as zero, so they were a baby. Women did give birth down there; women were obviously raped down there as well.

What sorts of responses have you had from readers?

It’s really interesting—some kids have read it who are younger than I would [expect], a couple of 10- and 11-year-olds have loved it. But it’s hearing from people who were miners, or have strong roots in mining, that means a lot to me because I’m not from the mining community. Yes, it is fiction, but I think it is important to try and make it feel right. I know the language is a barrier for some, definitely—one dyslexic person said [they] just couldn’t read it at all. Then I know others who were also severely dyslexic who tuned into it and loved it. It’s a Marmite book [the British yeast extract spread whose advertising slogan “You Either Love It Or Hate It” has entered the national lexicon]. I was expecting more haters, actually. I think it’s more interesting to have written a Marmite book.

How did you develop the language?

It’s playing with language from the Bible, there’s elements of Blake and Shakespeare. I did drama at university so I’m a big fan of Jacobean and Elizabethan playwrights and medieval plays like Everyman, so it’s a mishmash of different things. Dialects and accents here in the U.K. just fascinate me. Clee Hill [Shropshire] had a mining community and the miners came from all over, so they had almost their own separate dialect. Some of the dialect [in Bearmouth] is London—there’s definitely bits of Cockney rhyming slang—bits from Birmingham or Yorkshire, all sorts of places. Some people said to me early on that it reminded them of Riddley Walker [by Russell Hoban], which I had never read. It’s absolutely fantastic, but I’m very glad I hadn’t read it before I finished Bearmouth. It’s not the same at all, but there are elements that overlap, and I think I would have felt too intimidated.

To what degree were you thinking about contemporary social issues as you wrote?

Very much so. My Nan, one of her things that she always used to say was, “Who says?” It works for everything. What’s the agenda? In the era of fake news and the morality of manipulation, it’s a really interesting thing to have in the back of your head “why” and “who says?” Children, the minute they know what the word why means, that’s it—it’s unleashed. I think as adults sometimes we don’t always ask those questions, and we should; questioning things is how you bring about change. You learn by asking questions: You ask questions, you get answers, and then you might question those answers, but that’s how you learn. There’s a lot that we can still improve, right, so why wouldn’t we want to do that? Some people have said, “Oh, it’s a brave book.” But I think it’s brave for the publishers to publish it—it is a book that causes strong reactions, and I think it is a brave book to publish now, actually, as well, a book about revolution, one person making a difference.

Laura Simeon is a young readers’ editor.