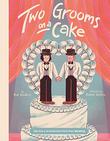

Let’s say you’re 6, finally 6 years old. You’re given Rob Sanders’ new picture book, Two Grooms on a Cake: The Story of America’s First Gay Wedding (Little Bee, May 4),whose cover features an illustration by Robbie Cathro of two male cake toppers—figurines that look just like Jack Baker and Michael McConnell, the two men who claim to be the first same-sex married couple in America. You are unaware that a simple Google search for “first same-sex marriage in America” reveals that on May 17, 2004, it was actually Marcia Kadish and Tanya McCloskey who were the first same-sex couple to get married in America.

So which couple has truly earned that distinction? For sheer craftiness and legal wiles, Baker and McConnell are the clear winners. In 1970, the couple was denied a marriage license in Hennepin County, Minnesota, so Baker, who was in law school, decided to legally change his name to the gender-neutral “Pat Lyn.” In 1971, McConnell went to a different location, Blue Earth County, to apply for a marriage license—alone, so that the clerk wouldn’t see that his spouse was a man. Minnesota’s marriage laws didn’t explicitly stipulate that marriage was outlawed between two people of the same sex, so Baker and McConnell were married. Once the officials in Blue Earth County realized their mistake, the county attorney told the clerk to not record the marriage, meaning that Michael and Jack McConnell (for they now had the same last name) couldn’t receive Social Security benefits or the other protections an officially recognized marriage confers. In 2018, after a long fight in the courts, a Minnesota judge ruled that the McConnells’ 1971 marriage was valid; not only was the couple entitled to spousal benefits, but they are officially the first legally married same-sex couple in America, and perhaps the world.

So which couple has truly earned that distinction? For sheer craftiness and legal wiles, Baker and McConnell are the clear winners. In 1970, the couple was denied a marriage license in Hennepin County, Minnesota, so Baker, who was in law school, decided to legally change his name to the gender-neutral “Pat Lyn.” In 1971, McConnell went to a different location, Blue Earth County, to apply for a marriage license—alone, so that the clerk wouldn’t see that his spouse was a man. Minnesota’s marriage laws didn’t explicitly stipulate that marriage was outlawed between two people of the same sex, so Baker and McConnell were married. Once the officials in Blue Earth County realized their mistake, the county attorney told the clerk to not record the marriage, meaning that Michael and Jack McConnell (for they now had the same last name) couldn’t receive Social Security benefits or the other protections an officially recognized marriage confers. In 2018, after a long fight in the courts, a Minnesota judge ruled that the McConnells’ 1971 marriage was valid; not only was the couple entitled to spousal benefits, but they are officially the first legally married same-sex couple in America, and perhaps the world.

How to make this set of tricky maneuvers and convoluted history perfectly clear to a young reader? For starters, Sanders, the author of a number of picture books about LGBTQ+ history, has the perfectly cute and approachable cake toppers who look like the McConnells narrate the book in the first person plural. But he also thought of his Aunt Shirley; she made wedding cakes for everyone in Sanders’ family. “The most interesting thing to me about a wedding then—maybe even now—is the cake,” says Sanders, who is 62. In the ’70s and ’80s, Aunt Shirley was in her baking heyday in Sanders’ home state of Missouri, and her cakes were dramatically tiered with fountains of colored water in them, “all those really tacky things by today's standards,” Sanders says. “I’ve seen them made with Crisco, which would make bakers today cringe. It was coat-your-mouth-and-stick-to-your-ribs kind of cake.”

With memories such as those, it’s no wonder Sanders thought of the careful tending required to make a cake taste and look beautiful as an analog to the watchful investment of love and selflessness that are necessary to make a relationship grow.

Like the McConnells, Sanders knows what it’s like to suffer from anti-gay discrimination. He grew up as a Southern Baptist and graduated from college with an elementary education degree. Then he attended seminary school. “I thought I was making a bargain with God, that I would go to seminary and he would make me not gay,” Sanders recalls. “That was my deal, to tell you the truth. We did not shake on it, so God did not keep his side of the bargain.”

Rob Sanders. Photo by Candy BarnhiselSanders was eventually hired by the publishing division of the Southern Baptist Convention, where he worked for approximately 15 years. The “best thing that happened to me,” Sanders says, was that he was outed and fired from the company. Sanders had been slowly coming out of the closet by then, disclosing his sexual orientation to a few friends and family. The night he was fired, his best friends took him out to dinner and they drank some champagne; earlier that day, he could’ve been fired for having alcohol at dinner. “My friends, especially my circle of gay friends, stood around me to make sure I realized what a positive turning point this could be for my life, and to embrace it,” Sanders says. He calls himself a “person of faith” but no longer participates in organized religion.

Rob Sanders. Photo by Candy BarnhiselSanders was eventually hired by the publishing division of the Southern Baptist Convention, where he worked for approximately 15 years. The “best thing that happened to me,” Sanders says, was that he was outed and fired from the company. Sanders had been slowly coming out of the closet by then, disclosing his sexual orientation to a few friends and family. The night he was fired, his best friends took him out to dinner and they drank some champagne; earlier that day, he could’ve been fired for having alcohol at dinner. “My friends, especially my circle of gay friends, stood around me to make sure I realized what a positive turning point this could be for my life, and to embrace it,” Sanders says. He calls himself a “person of faith” but no longer participates in organized religion.

When the McConnells were married, Sanders was 13, “beginning to awaken to who I was,” he reflects. “The sheer thought that these guys had the courage to do what they did” continues to inspire the author. The McConnells were doing much more than applying for a marriage license, he points out; they were insisting that they be treated just like any other person wanting to get married. “It’s inspirational to me because I know what my life was like in Springfield, Missouri,” Sanders says. “Their bravery has really changed my perspective.”

Claiborne Smith is the literary director of the San Antonio Book Festival and the former editor-in-chief of Kirkus Reviews.