Here is the truly amazing thing that few people besides Tommie Smith remember about his gold medal–winning 200-meter run in the 1968 Olympics: He broke the world record in just under 20 seconds on one good leg.

Smith, then 24 and one of America’s track-and-field elite, had badly pulled a groin muscle just as he’d crossed the finish line of a semifinal heat a couple hours before.

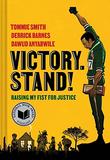

“It was a ligament, just above my left leg,” Smith, now 78, recalls during a phone interview about his graphic memoir, Victory. Stand!: Raising My Fist for Justice (Norton Young Readers, Sept. 27).

“I injured it by slowing down on a curve. I forgot that slowing down is as important as taking off,” Smith says. “If the finals had been [held] the next day, I could not have run that race.” Through intense concentration, canny athleticism, and sheer will, Smith edged his friend and teammate John Carlos and Australian Peter Norman at the tape, with Norman finishing second and Carlos finishing third.

What happened shortly afterward that Oct. 16 in Mexico City was of such magnitude that it all but swept away every other detail of Smith’s improbable triumph.

By twilight, as Smith and Carlos ascended the victory stand to accept their gold and bronze medals, they had removed their track shoes and put black leather gloves on one hand each. As “The Star-Spangled Banner” played, both Black American athletes bowed their heads to their nation’s flag and raised their gloved fists to the darkening skies in silent protest against racial injustice.

Almost everything in Tommie Smith’s life that led up to that seminal moment, along with much of the fury, ostracism, and, eventually, lasting glory that happened in its wake, is chronicled in Victory. Stand! Smith, now retired from 27 years of teaching and coaching at Santa Monica College and living in Georgia, collaborated with award-winning writer Derrick Barnes (Crown: An Ode to the Fresh Cut) and artist Dawud Anyabwile (Rebound) on the book and its black-and-white illustrations. This week, the book made the longlist for the National Book Award for young people’s literature.

Having already published an autobiography for adults (Silent Gesture, 2008), Smith was at first reluctant to tell his story again in book form. Eventually, he says, “I was convinced that both the writer and the illustrator would be great at making my story understood to kids, to be told in a manner that would make them feel a part of my own life. And to make [a child], when they read this, say to themselves, ‘Gee, I need more than what I got.’ Because that was how I felt growing up and coming to that moment in my life when I did what I had to do.”

The 200-meter final in Mexico City is used as a framing device for Smith’s life story, from his impoverished childhood in rural Red River County, Texas, as the seventh of 12 children born to a sharecropper and his wife. (In the book, Smith describes his young self as “antsy, a bright ball of energy that found it hard to be still.”) The family migrated to Lemoore, California, near the San Joaquin Valley, where young Tommie attended racially integrated schools, including the local high school where he first showed promise as a multisport athlete and won a scholarship to San Jose State University in 1963.

The 200-meter final in Mexico City is used as a framing device for Smith’s life story, from his impoverished childhood in rural Red River County, Texas, as the seventh of 12 children born to a sharecropper and his wife. (In the book, Smith describes his young self as “antsy, a bright ball of energy that found it hard to be still.”) The family migrated to Lemoore, California, near the San Joaquin Valley, where young Tommie attended racially integrated schools, including the local high school where he first showed promise as a multisport athlete and won a scholarship to San Jose State University in 1963.

Although he and his family didn’t talk about segregation or politics when he was a child, Smith entered his 20s with a burgeoning social consciousness fed by the civil rights movement of the early ’60s. “I had an obligation,” he writes, “not just to carry the banner for San Jose State, during track meets. I was obligated to carry an even larger banner for my people.”

Originally, Smith, Carlos, and other Black track stars intended to boycott the 1968 Games as protest. The virulent, sometimes violent reactions from Whites toward that prospect (including death threats and hate mail sent to Smith and other protesting athletes) anticipated the wave of negative reactions against Smith and Carlos’ silent demonstration. Both were suspended from the games by the U.S. Olympic Committee and given 48 hours to head back to the States. Before Smith reached home, he’d been fired from a part-time job he had at a Pontiac dealership. And that was only the beginning.

“I was banned from any competition in Europe representing the United States,” he recalls. “I couldn’t run under the flag in the U.S. I needed to move on. And I had to support a family. I was 24 years old, married with a son, and there was no time to wait for somebody to give me handouts, and I was at the peak of my career as a track-and-field athlete.” He got teaching jobs in public schools and, in 1972, landed a coaching position at Oberlin College, where he worked for six years before moving back to California and Santa Monica College.

After the turn of the 21st century, Smith and Carlos received belated accolades and honors, including the Arthur Ashe Award for Courage at the 2008 ESPY Awards, formal recognition of their courage at the White House by President Barack Obama in 2016, and commemorative statues of Smith and Carlos’ Olympic salute at both the National Museum of African American History in Washington and on the San Jose State campus.

Victory. Stand! is part of what seems an ongoing process of reacquainting the world with Tommie Smith, who confesses with mild amusement that the book has given even him an opportunity to reacquaint himself with the child, the man, the athlete, and hero he’s become.

“It tickles me. My life used to frustrate me, used to scare me,” Smith says. “Now I can see myself from the inside out.”

Gene Seymour is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn and has written for the Nation, the Washington Post, and CNN.com.